2001, and its many unhappy children

By Sriman Narayanan

I’ve always felt, as a writer, that science fiction gets to cheat in storytelling. The rest of us need to find a way to imbue our stories with importance. But how could an exploding star, interstellar travel or alien visitors be inconsequential?

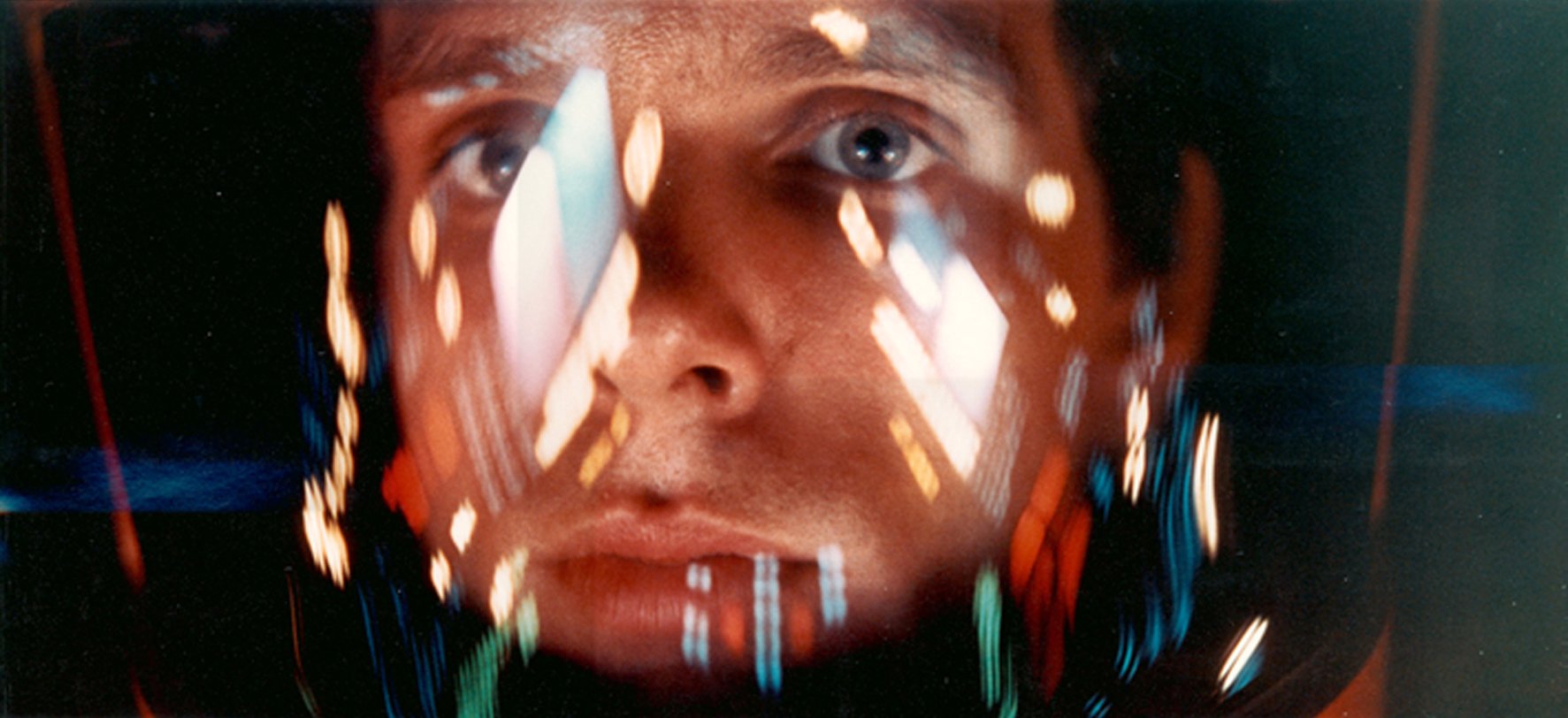

Drama is assumed as inherently parceled with every space flick we buy tickets to see. It comes with a dramatic score and lofty thematic conclusions. But is that something we, innately terrified and enamored with the night sky, assigned to the genre? Or does that, at least in part, have to do with 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Stanley Kubrick, in the sixty years following the film’s release, has been elevated to a status of director godhood. Among the dividends paid by this status are multiple generations of filmgoers that will preemptively give you every benefit of every doubt: I will sit through ten minutes of black screen because you are Stanley Kubrick, and I assume you know what you’re doing.

This godhood status informs the viewer, also, that we should read deeply into each of the decisions nested within a film’s gargantuan runtime. Because that’s what they are, decisions. Every actor, producer or family testimony leads to a portraiture of Kubrick that is ruthlessly precise; if we look behind these decisions, we may just know their motives, and peel back the layers further to understand this film that appears deeply indifferent to allowing us explanation.

Answers to the film’s questions are how Roger Ebert understood 2001 – in 1968, anyway. He believed it to be a parable, and that the film was a story housing a story. In his original piece, “2001" -- The Monolith and the Message,” he narrows the film into its answers. This is what a monolith is. This is what these decisions mean. This is what the story is trying to say.

By the time he revisited the film in 1997, though, his thoughts had seemingly evolved, and he appeared to understand 2001 more as a piece of image-making, but he was still convinced that the film’s power lay in Kubrick’s decisions.

This relationship change is familiar for filmgoers and their adored films, and especially so when considering a film as stupefying as 2001. Upon its release, we attempt to understand any movie in the context of its peers. As time stretches, the film makes itself comfortable in the mind, we stick it in the back pocket and carry it with us to the grocery store, are reminded of its bump when laid face-up on lawns, where we stare up at the stars we’re allowed to see. We do not wonder, in those moments, where Kubrick’s monolith came from. We just wonder.

I was not alive in 1968, and so my context for watching 2001 comes after the wealth of great science fiction filmmaking I became obsessed with as a teenager: Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival, Blade Runner 2049 and Dune, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Alex Garland’s Ex Machina. The language I spoke upon my first interaction with 2001 was the language of those films.

2001 finds its visual language repeated today. What even is the genre without muted colors, dark shadows, sparse highlights? Without grand orchestration? Without stoic leads? Without blunt monologue? Without ambiguity? But more interesting is what the 21st century’s science fiction is decidedly not.

Ebert alludes to the starchild at the film’s close as a point of purpose, both innately within the film, and extrinsically offered for the viewer. He writes of man’s fate, “he will then become a child again, but a child of an infinitely more advanced, more ancient race, just as apes once became, to their own dismay, the infant stage of man.” 2001, though, rejects the idea that humans are grandiose in their current state. Bowman is whipped around mercilessly by the universe and is left in what Ebert imagines as a zoo at the film’s close. He is not an agent. This conclusion, while broadly hopeful for the state of consciousness, may arrive as rather hopeless for those who otherwise may have taken for granted their own individual grandiosity.

Christopher Nolan said he was seven when he watched 2001 for the first time. His film Interstellar is a melodramatically human narrative at the center of a cosmos that appears, ultimately, sympathetic to its residents. This is philosophically perverse when compared to 2001’s understanding of the cosmos, which is brutal and indifferent, only elegant when humans are uninvolved.

Denis Villeneuve said he “first watched [2001] from the staircase.” He appears more closely in tune with Space Odyssey’s chill than Nolan, but he, too, finds value in the individual that 2001 avoids. His 2016 film Arrival takes a mostly stoic lead in Amy Adams and offers her a dramatic ending, one where visitors offer her the gift of foresight because her skills are valued. His 2017 film Blade Runner 2049 finds universal meaning in the individual, because even if one is not prophesied to be the “chosen one,” he still has a role to play.

Alex Garland said, “I’m not sure there isn’t a fundamental discussion of issues to do with AI that isn’t already and better dealt with in 2001,” and yet his AI film Ex Machina exists in entire opposition to 2001’s Hal. Garland believes Ava, his example of a conscious being, is ethically “good,” and he believes Hal is “neutral.”

But the conversation is not exactly intellectual debate, and not really even conversation. It would be more accurate to describe as spiritual insistence – Nolan and Villeneuve and Garland are focused on shaking the ghost of their artistic father, insisting that their individual human lives do have meaning on the largest scales. These films are made by the boys who allowed the film to “wash over” them, as Nolan described, they emphasize a grappling with the “cinematic shock” of being told their lives do not matter if they are to one day be replaced by a giant star baby, as Villeneuve explained. The effect is a landscape of contemporary science fiction cinema that’s ultimately humanist. Not because Kubrick intended to make it that way, but because he didn’t.

The experience of 2001: A Space Odyssey cannot be distilled into the confines of what we normally ask film to be. We cannot measure the victories of the film within just the bounds of decision-making.

The film is alive, has dug molds into the minds crafting today’s universe. Most of us will never be with the stars, so this is how we will know their cosmos. And for those whose brains receive the deepest impressions, they have hoped – will continue to hope – to pour their own language back into those recesses, wait for them to solidify, and return a hardened response to the world.